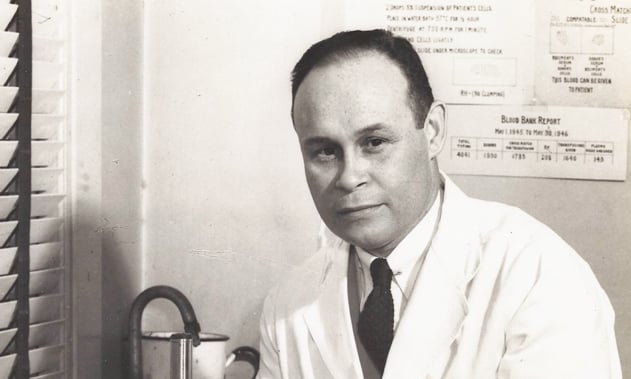

Charles R. Drew was the man who improved blood storage and distribution techniques. His innovation helped save many Allied troops in World War II. But did you know he resigned from the Red Cross?

Charles Richard Drew, the African-American surgeon who pioneered the technology on blood storage, was also the chief of the first American Red Cross Blood Bank. He resigned from the position because of a protocol where black blood would be separated from white blood.

Who was Charles R. Drew?

Charles Drew was born on June 3, 1904. He grew up in Washington, DC. Growing up in a low-income family, Drew contributed to the household income by delivering newspapers in the neighborhood. His ability to coordinate and manage people helped him, and ten of his friends create a network to deliver 2,000 newspapers daily.

Drew attended the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, a historically Black school. He excelled in all the sports he joined, landing a partial scholarship at Amherst College in Massachusetts in 1922. He also excelled in both track and football, earning the Howard Hill Mossman and Thomas W. Ashley trophies for the college. By 1926 Drew graduated and was one of only sixteen African Americans who did at that time.

Drew took up medicine in 1928 at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. He chose the University over being on the waitlist of Harvard University. In 1933, he received his degrees of Doctor of Medicine and Master of Surgery. He did his internship in the Royal Victoria and Montreal General Hospitals but soon moved to Howard University as an instructor in Pathology due to his father’s death in 1934. (Source: NCBI)

Drew continued his medical career, creating the first two blood banks and eventually becoming the head of Howard University’s surgery department. He became the chief surgeon at Freedmen’s Hospital and became the first African American examiner for the American Board of Surgery.

Drew received the 1943 Spingarn Medal for the highest and noblest achievement to recognize his blood plasma collection and distribution work. Dr. Drew passed away on April 1, 1950, at forty-five. Drew and three other colleagues attended a medical conference at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. His vehicle crashed in nearby Burlington, Alabama, ending his life.

Drew accepted several posthumous honors and was even included in the 1981 USPS Great Americans stamp series. (Source: Biography)

The Discriminatory Protocol

Drew developed a method for processing and preserving blood plasma or blood without cells. Plasma lasts much longer than whole blood, making it possible to be stored or banked for more extended periods. Drew was asked to head a special medical effort known as Blood for Britain with his development of blood plasma. He organized sending blood plasma across the seas to treat casualties of war.

In 1941, Drew again headed another blood bank effort for the Red Cross. The action was to be used for U.S. personnel. He soon became frustrated as the army did not want to use African American blood, causing him to resign from his post. (Source: Biography)

Drew was the most prominent figure in the field of blood banking. He was not about to let all his hard work go to waste when protocol dictated that black people’s blood be separated from white blood. There were absolutely no scientific bases to do so, and Drew protested against the policy and resigned from his position with the American Red Cross. The organization maintained the protocol up until 1950. (Source: NCBI)