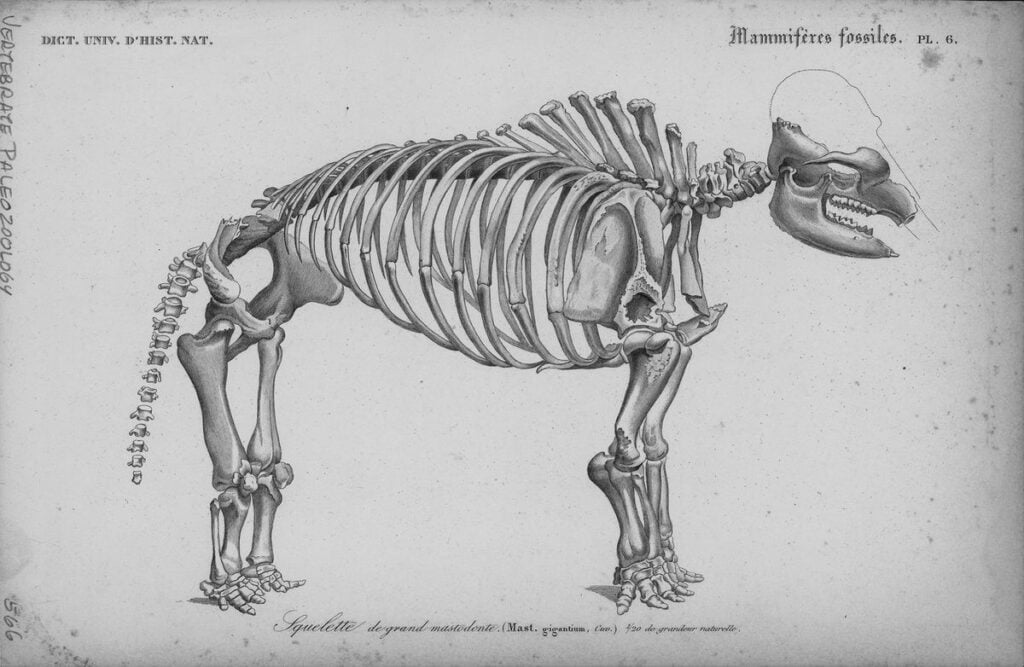

Mastodons are extinct proboscideans from the late Miocene or late Pliocene that lived in North and Central America from the late Miocene to the end of the Pleistocene 10,000 to 11,000 years ago. Mastodons were primarily forest dwellers who lived in herds. But did you know who asked Lewis and Clark to bring back living Mastodons to the United States?

Thomas Jefferson believed that animal species could not become extinct and that Mastodons, giant sloths, and dinosaurs existed in the American West. He requested that Lewis and Clark bring back living Mastodons.

Thomas Jefferson, the Extinction Non-Believer

Thomas Jefferson avidly collected such accounts because they were critical to his understanding of science. Jefferson did not believe in the concept of extinction. He was especially fascinated by the American mastodon, the elephant relative he referred to as “the mammoth” for many years. It wasn’t until 1806 in Paris that the French naturalist Georges Cuvier formally separated mastodonte from mammoth and concluded that there were two living elephant species.

However, Jefferson had already concluded in his Notes on the State of Virginia that the cold-adapted mammoths were distinct from the living tropical African and Asian elephants. He amassed an extensive collection of “mammoth” remains over many years, which he displayed in the entrance hall of Monticello, his great house in Virginia.

Gaylord Simpson points out that Jefferson did not believe in extinction for religious reasons and that in his paper on Megalonyx, he began with a theory that the animal was some gigantic American lion and then attempted to prove it by first gathering facts. Both of these accusations are true. However, the situation is far more complicated than Simpson anticipated.

Jefferson recognized the obvious fact that species and populations became extinct, such as the wolf and bear in Britain or various American Indian groups. He also believed that such losses were compensated for by nature.

In the case of the mastodon and Megalonyx, Jefferson, the lawyer, stated that the bones exist; therefore, the animal has existed. If this animal has once existed, it is probable that he still exists. However, he also argued like a scientist. He devoted four out of fourteen pages of his Megalonyx paper to reports from western travelers of encounters like the ones described above. In this sense, his view of extinction can be viewed as a hypothesis supported by evidence.

A more difficult question concerns Jefferson’s perception of his mastodon and Megalonyx bones. A careful search of Jefferson’s writings which are now made possible by the availability of searchable databases, reveals that he never referred to them as fossils. For him, they were always just bones, and neither Notes on the State of Virginia nor his letters contain the word fossil. (Source: The American Scientist)

Thomas Jefferson, the Father of American Vertebrate Paleontology?

Historians have dubbed Jefferson the Father of American Vertebrate Paleontology for his analysis of the mastodon and description of Megalonyx. However, paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson argued 65 years ago in a masterful review of American vertebrate paleontology history that Jefferson did not deserve this honor because his actions were not sufficiently scientific. (Source: The American Scientist)